The zombie genre is a ubiquitous force in 2025. Just take a look around. From television to video games to mega-franchises like The Walking Dead, The Last of Us, and 28 Days Later—the sequel of which, 28 Years Later, is in theaters now—the undead are as culturally rich and fascinating to audiences as ever before. But before zombies were sprinting through pop culture—metaphors for consumerism and fascism—they had a totally different association. They were an element of Haitian folklore repackaged through through the lens of colonial anxieties. Zombies were not the flesh-eating monsters we’re not familiar with, but bodies effected by magic that removed their autonomy and made them vessels of control.

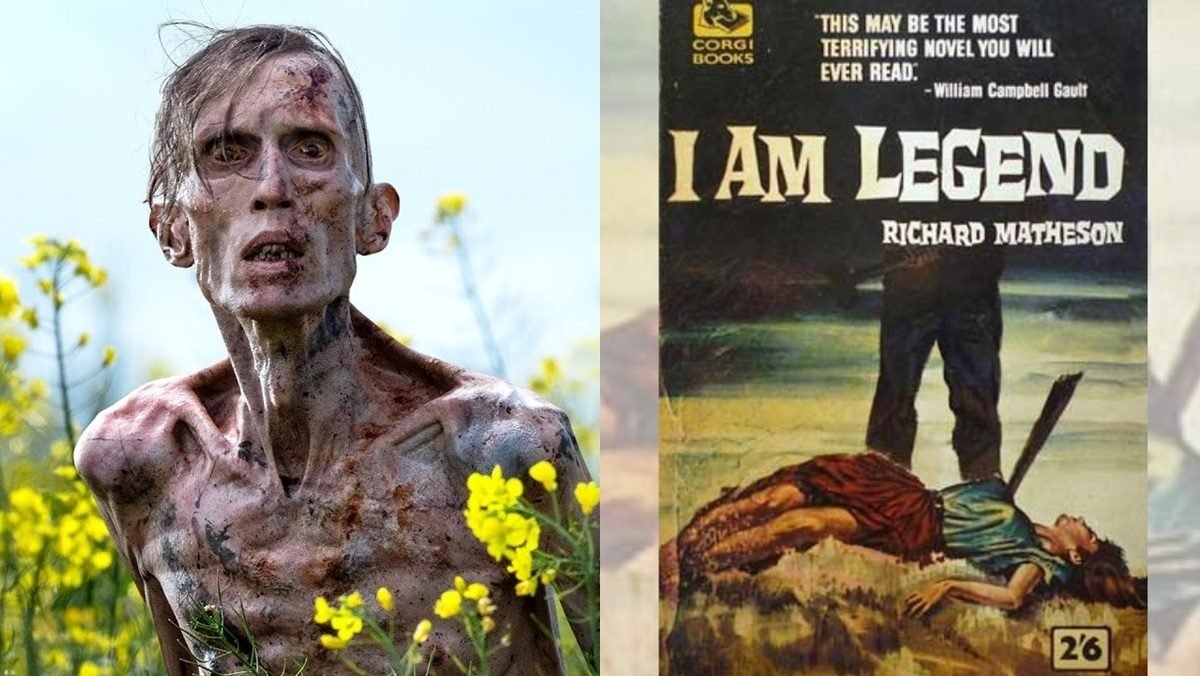

The shift to how we now recognize zombies happened in the middle of the 20th century with Richard Matheson’s seminal 1954 horror novel I Am Legend. Originally categorized a vampire fiction, Matheson’s story was in fact the true beginning of the modern zombie; ravenous and infected flesh-eaters. George A. Romero, credited with bringing this version of the zombie to the big screen, cited I Am Legend as his primary inspiration for his 1968 film Night of the Living Dead. “I had written a short story, which I basically had ripped off from a Richard Matheson novel called I Am Legend,” Romero says in the documentary One for the Fire: The Legacy of Night of the Living Dead, found on the film’s original Blu-ray release.

Romero’s totemic film influenced all that came next, but it’s important to acknowledge the source text. To better understand how we got from Haitian sugar plantations to the mushroom apocalypse of The Last of Us, let’s take a deeper look at the origins of the zombie and how Matheson totally reinvented how we see the creatures.

From Hoodoo to Hollywood

‘I don’t care. I don’t have to. I don’t have to do anything.” – I Am Legend

The idea of the zombie entered American consciousness through early 20th-century accounts of Haitian Vodou, a religion that developed in Haiti and blends West and Central African spiritual traditions with Roman Catholicism. Books like William Seabrook’s The Magic Island (1929) and films like White Zombie (1932) portrayed the zombie as “slaves”, freshly dead bodies revived through magic to carry out the deeds of their necromancers. But most of these depictions were not grounded in real history, but rather racist caricatures of Haitian culture that expressed colonist fears of retribution and racial otherness. (The dehumanization of Haitians continues in modern-day America, where they remain scapegoats for white supremacist anxieties.)

The perception of zombies changed when horror started intersecting with the Cold War-era. Nuclear fallout and the associated fallout of it—including radiation poisoning and mass extinction—became the centerpiece of fictional horror storytelling. The perfect ingredients for a new monster to emerge.

The Genesis of I Am Legend

“In a world of monotonous horror there could be no salvation in wild dreaming.” – I Am Legend

I Am Legend is set in Los Angeles somewhere in the near future and follows Robert Neville, the “last man on Earth” after a widespread infection killed all other humans. But these dead bodies didn’t stay dead. In this version of the apocalypse, the ill reanimate shortly after death, bloodthirsty husks of their former selves.

By day, Neville fortifies his home, scavenges supplies, and kills the sleeping “vampires” (as they’re referred to in the novel) with wooden stakes, which immediately liquifies them. By night, he hides in his barricaded house as the infected emerge from hiding and try to lure him out. As the story progresses, we learn more about the arrival of the disease and the horrifying way it claimed the lives of Neville’s wife and young daughter. He is a man tormented not just by this impossible new reality, but by the incomprehensible grief that only he will ever understand.

Because of this, Neville slowly unravels. He succumbs to alcoholism and loses touch with reality. He fears what he’s becoming, even though he’s somehow immune to the true horrors. What does it mean to be the sole survivor of a world-ending plague? What does it mean to be haunted by the formerly living, who are conscious enough to know who Neville is, but dead enough to feel like empty imitations of the people he once loved?

The Science of Horror

Matheson peppers the novel with incredible and revelatory detail. The novel suggests a scientific explanation for the state of the world: a bacterial infection that erodes the body and mind, turning diseased people into these vampiric creatures. Many of the traditional vampire tropes are there—allergies to garlic, an inability to withstand sunlight, a fear of crosses—but the element of disease is new. There is also some nuance, as the novel slowly reveals. There aren’t just the dead, reanimated bodies, but also “living” vampires—infected people who have the traits of the undead (they are nocturnal and also husk-like) but are still technically breathing. This range of symptoms, and the viral outbreak nature of the story, is something that still exists in zombie fiction.

Eventually, Neville captures a woman he believes to be uninfected, only to later discover she is a spy sent by a new society of infected who have formed their own culture and see him as the true monster. That’s where the novel takes its name, and is another thing present in modern zombie storytelling. When most of the world is made up of reanimated corpses, it’s the survivors who become monstrous through inversion.

Vampires or Zombies?

“Normalcy was a majority concept, the standard of many and not the standard of just one man.” – I Am Legend

While I Am Legend refers to its creatures as vampires, their behavior and the novel’s framing create what would become standard zombie tropes. Matheson’s zombies are numerous, mindless, and predatory. They return each night to scratch at Neville’s front door, taunting him. (One of the more evocatively horrifying recurring elements of the novel.) There are no “master” vampires as there are in most vampire tales. No one big bad guy to kill that allows a human hero to emerge. Instead, it’s an ugly and untamed reality. A mass epidemic that is so widespread it’s impossible to contain. It’s not about conquering, it’s about accepting a new reality.

This blend of vampire and zombie is a fascinating concoction. It evolves both away from their mythical origins and creates a new kind of creature tethered to very modern concerns of pandemics and social isolation. The shift in tone from gothic to post-apocalyptic continues to shape the undead genre.

Night of the Living Dead, and the Zombie Blueprint

“The world’s gone mad and I’m part of the madness.” —I Am Legend

As mentioned above, Romero didn’t hide Matheson’s influenced on his zombie franchise. Night of the Living Dead took the premise of I Am Legend and democratized it. It’s not just one man against a mass hoard of reanimated corpses, but a story of community told via a group of survivors. The word “zombie” is never said aloud but Romero’s living dead exhibit many of the traits Matheson introduced.

Romero also famously used zombies as political metaphor, something less present in I Am Legend. The racial tensions in Night of the Living Dead, especially in the context of 1960s America, made the genre a vessel for social commentary. But the blueprint—the swaths of infected, a crumbling civilization, and the existential dread that comes with such an Earth-shattering event—is straight from Matheson.

The [Unfortunate] Impact of 2007’s I Am Legend

“Maybe the world didn’t go to hell. Maybe it was just me.” – I Am Legend (Film)

Romero’s films were loosely inspired by Matheson’s novel, but there have also been several straight-up adaptations, including 1964’s The Last Man on Earth and 1971’s The Omega Man. But the best-known version, at least to 21st-century audiences, is 2007’s Will-Smith-starring I Am Legend.

While the film brought the novel back into public consciousness, it arguably did more harm than good to its legacy. While it retains the basic premise—Neville as the last man on Earth in the midst of a zombie apocalypse—it alters the tone and basically everything else. The monsters are CGI mutants who are more rabid animal than former humans, which also eliminates a lot of the existential tragedy of the original story. The title even makes less sense in this version, because Neville never really has the revelation that he’s the legendary one now. Instead, he has a pretty standard Hollywood hero arc where he finds a cure for the living infected and sacrifices himself for the greater good.

Your mileage may vary on the quality of the film. It certainly has its defenders, and adaptations needn’t be beat-for-beat reproductions of a source text. But the beauty of the novel rests in the ambiguity of monstrosity, and the evolution of our understanding of humanity’s role in the history of the world. Matheson’s point—and arguably Romero’s, as there’s no real political through line—is lost in a sea of fast-action, ugly computerized visuals, and a conventional ending that only dumbs down the story it’s trying to emulate.

Why I Am Legend Still Matters

“I am legend.” – I Am Legend

Matheson’s influence is, as already established, pretty much everywhere. In 28 Days Later and its upcoming sequel 28 Years Later, we see the same vision of a world overrun by infection and not the supernatural. Screenwriter Alex Garland and director Danny Boyle’s infected are fast, but the existential despair of the situation traces back to I Am Legend. And The Last of Us has similarly shared DNA. The cordyceps outbreak and the focus on character-driven drama feel like spiritual successors to Neville’s crisis.

Reading I Am Legend in 2025 is a fascinating journey, and one any true-blue horror fan should take. Even if Matheson’s writing feels dated or the story replayed, it’s important historical context for those curious about the progression of the undead in fictional. In fact, the novel feels almost more relevant than many of the aforementioned titles in the modern context, because it resists things like exploring scientific specifics and tidy answers in general. The book doesn’t have a savior or cure. It is, rather simply, about a man whose world ended, who tried to hold on, and who ultimately learned he was no longer part of it.

Humanity in the Darkest Moments

But I Am Legend is also a novel that confronts a very real aspect of humanity: that we are all living alongside death. Everyone we love will die. Many already have. We’ll all die, too. It’s customary to bury or burn the dead, and with them the secrets they carry about mortality. When bodies are out of sight and out of mind, we don’t have to think so much about the reality of mishandled pandemics, scientific ignorance, or even more personal details like scores never settled, conversations never head. The dead become a thing of the past.

But zombies don’t let us off so easy. Death is a confrontation. Our dead loved ones tap at the door, taunting us, forcing us to acknowledge what’s easier to memorialize instead of understand. Their diseased bodies make scientific reality inescapable. They are more horrifying for what they reveal instead of what they consume. Matheson brought the conversation to the forefront, but the other chapters are still being written.

The post 28 YEARS LATER and Counting: The Undying Influence of Richard Matheson’s I AM LEGEND appeared first on Nerdist.

This articles is written by : Nermeen Nabil Khear Abdelmalak

All rights reserved to : USAGOLDMIES . www.usagoldmines.com

You can Enjoy surfing our website categories and read more content in many fields you may like .

Why USAGoldMines ?

USAGoldMines is a comprehensive website offering the latest in financial, crypto, and technical news. With specialized sections for each category, it provides readers with up-to-date market insights, investment trends, and technological advancements, making it a valuable resource for investors and enthusiasts in the fast-paced financial world.