In 1958, the American free-market economist Leonard E Read published his famous essay I, Pencil, in which he made his point about the interconnected nature of free market economics by following everything, and we mean Everything, that went into the manufacture of the humble writing instrument.

I thought about the essay last week when I wrote a piece about a new Chinese microcontroller with an integrated driver for small motors, because a commenter asked me why I was featuring a non-American part. As a Brit I remarked that it would look a bit silly were I were to only feature parts made in dear old Blighty — yes, we do still make some semiconductors! — and it made more sense to feature cool parts wherever I found them. But it left me musing about the nature of semiconductors, and whether it’s possible for any of them to truly only come from one country. So here follows a much more functional I, Chip than Read’s original, trying to work out just where your integrated circuit really comes from. It almost certainly takes great liberties with the details of the processes involved, but the countries of manufacture and extraction are accurate.

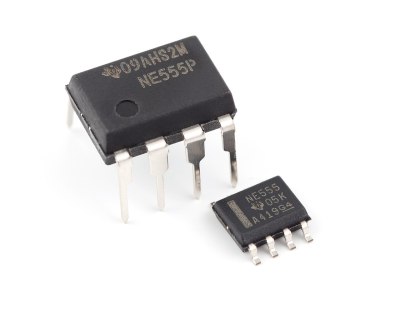

First, There’s The Silicon

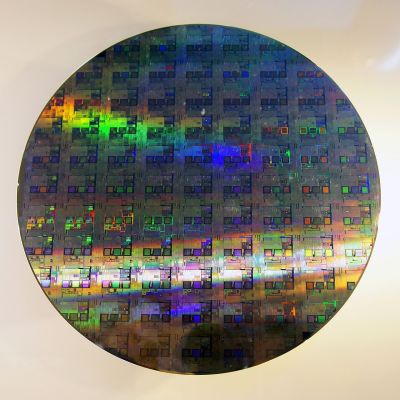

An integrated circuit, or silicon chip, is as its name suggests, made of silicon. Silicon is all around us in rocks and minerals, as silicon dioxide, which we know in impure form as sand. The world’s largest producer of silicon metal is China, followed by Russia, then Brazil. So if China and Russia are off the table then somewhere in Brazil, a Korean-made continuous bucket excavator scoops up some sand from a quarry.

That sand is taken to a smelting plant and fed with some carbon, probably petroleum coke as a by-product from a Brazilian oil refinery, into a Taiwanese-made submerged-arc furnace. The smelting plant produces ingots of impure silicon, which are shipped to a wafer plant in Taiwan. There they pass through a German-made zone refining process to produce the ultra-pure silicon which is split into wafers. Taiwan is a global centre for semiconductor foundries so the wafers could be shipped locally, but our chip is going to be made in the USA. They’re packed in a carton made from Canadian wood pulp, and placed in a container on a Korean-made ship bound for an American port. There it’s unloaded by a German-made container handling crane, and placed on a truck for transport to the foundry. The truck is American, made in the great state of Washington.

Then, There’s The Package And Leads

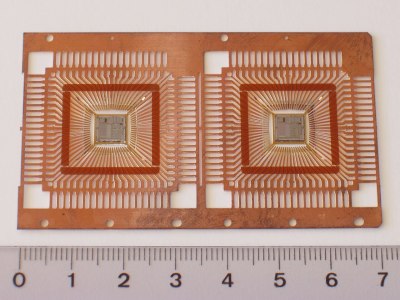

Our integrated circuit is the chip itself, but in most cases it’s not just the bare chip. It’s supplied potted in an epoxy case, and with its contacts brought out to some kind of pins. The epoxy is a petrochemical product, while the lead frame is either stamped or chemically etched from metal sheet and plated.

So, somewhere in the Chilean Atacama desert, an American-made dragline excavator is digging out copper ore from the bottom of a huge pit. The ore is loaded into Japanese-made dump trucks, from where it’s driven to a rail head and loaded into ore carrier cars. The American-made locomotives take it to a refining plant where machinery installed by a Finnish company smelts and refines it into copper ingots. These are shipped to Sweden aboard a German-made ship, unloaded by a German-made crane, and delivered to a specialised metal refiner on a Swedish-made truck.

Meanwhile underground in Ontario, Canada, Swedish-made machinery scoops up nickel ore and loads it onto a Swedish-made mine truck. At the nickel refining plant, which is Canadian-made, the sulphur and iron impurities are removed, and the resulting nickel ingots travel by rail behind a Canadian-made (but American designed) locomotive to a port, where an American made crane loads them into an Italian-made ship bound for Sweden. Another German crane and Swedish truck deliver it to the metal refiner, where a Swedish-made plant is used to create a copper-nickel alloy.

A German-made rolling plant then turns the alloy into a thin sheet, shipped in a roll inside a container on a Japanese-made container ship bound for the USA. Eventually after another round of cranes, trains, and trucks, all American this time, it arrives at the company who makes lead frames. They use a Japanese-made machine to stamp the sheet alloy and create the frames themselves. An American-made truck delivers them to the chip foundry.

At a petrochemical plant in China, bulk epoxy resin, plasticisers, pigments, and other products are manufactured. They are supplied in drums, which are shipped on a Chinese-made container ship to an American port where American cranes and trucks do the job of delivering them to an epoxy formulation company. There they are mixed in carefully-selected proportions to produce American-made epoxy semiconductor moulding compound, which is delivered to the chip foundry on an American-made truck.

Bringing all Those Countries’ Parts Together

The foundry now has the silicon wafers, lead frames, and epoxy it needs to make an integrated circuit. There are many other chemicals used in its process, but for simplicity we’ll take those three as being the parts which make an IC. What they don’t yet have is an integrated circuit to make. For that there’s a team of high-end engineers in a smart air-conditioned office of an American semiconductor company in California. They are integrated circuit designers, but they don’t design everything. Instead they buy in much of the circuit as intellectual property, which can come from a variety of different countries. Banging the drum as a Brit I’m sure you’ll all know that ARM cores come from Cambridge here in the UK, just to name the most obvious example. So British, German, Dutch, American, and Canadian IP is combined using American software and the knowledge of American engineers, and the resulting design is sent to the foundry.

The process machinery of an integrated circuit foundry lies probably at the most bleeding edge of human technology. The machines this foundry uses are mostly from Eindhoven in the Netherlands, but they are joined by American, German, Japanese, and even British ones. Even then, those machines themselves contain high-precision parts from all those countries and more, so that Dutch machine is also in part American and German too.

Whatever magic the semiconductor foundry does is performed, and at the loading bay appear cartons made from Canadian wood pulp containing reels made from Chinese bulk polymer, that have hundreds of packaged American-made integrated circuits in them. Some of them are shipped on an American truck to an airport, from where they cross the Atlantic in the hold of a pan-European-manufactured jet aircraft to be shipped from the British airport in a German-made truck to an electronics distributor in Northamptonshire. I place an order, and the next day a Polish bloke driving an American-badged van that was made in Turkey delivers a few of them to my door.

The above path from a dusty quarry in Brazil to my front door in Oxfordshire is excessively simplified, and were you to really try to find every possible global contribution it’s likely there would be few countries left out and this document would be hundreds of pages long. I hope mining engineers, metallurgists, chemists, and semiconductor process engineers will forgive me for any omissions or errors. What I hope it does illustrate though is how connected the world of manufacturing is, and how many sources come together to produce a single product. Read’s 1958 pencil is alive and well..

Header image: Mister rf, CC BY-SA 4.0.

This articles is written by : Nermeen Nabil Khear Abdelmalak

All rights reserved to : USAGOLDMIES . www.usagoldmines.com

You can Enjoy surfing our website categories and read more content in many fields you may like .

Why USAGoldMines ?

USAGoldMines is a comprehensive website offering the latest in financial, crypto, and technical news. With specialized sections for each category, it provides readers with up-to-date market insights, investment trends, and technological advancements, making it a valuable resource for investors and enthusiasts in the fast-paced financial world.