Anyone who has spent any amount of time in or near people who are really interested in energy policies will have heard proclamations such as that ‘baseload is dead’ and the sorting of energy sources by parameters like their levelized cost of energy (LCoE) and merit order. Another thing that one may have noticed here is that this is also an area where debates and arguments can get pretty heated.

The confusing thing is that depending on where you look, you will find wildly different claims. This raises many questions, not only about where the actual truth lies, but also about the fundamentals. Within a statement such as that ‘baseload is dead’ there lie a lot of unanswered questions, such as what baseload actually is, and why it has to die.

Upon exploring these topics we quickly drown in terms like ‘load-following’ and ‘dispatchable power’, all of which are part of a healthy grid, but which to the average person sound as logical and easy to follow as a discussion on stock trading, with a similar level of mysticism. Let’s fix that.

Loading The Bases

Baseload is the lowest continuously expected demand, which sets the minimum required amount of power generating capacity that needs to be always online and powering the grid. Hence the ‘base’ part, and thus clearly not something that can be ‘dead’, since this base demand is still there.

What the claim of ‘baseload is dead’ comes from is the idea that with new types of generation that we are adding today, we do not need special baseload generators any more. After all, if the entire grid and the connected generators can respond dynamically to any demand change, then you do not need to keep special baseload plants around, as they have become obsolete.

A baseload plant is what is what we traditionally call power plants that are designed to run at 100% output or close to it for as long as they can, usually between refueling and/or maintenance cycles. These are generally thermal plants, powered by coal or nuclear fuel, as this makes the most economical use of their generating capacity, and thus for the cheapest form of dispatchable power on the grid.

With only dispatchable generators on the grid this was very predictable, with any peaks handled by dedicated power plants, both load-following and peaking power plants. This all changed when large-scale solar and wind generators were introduced, and with it the duck curve was born.

As both the sun and wind are generally more prevalent during the day, and these generators are not generally curtailed, this means that suddenly everything else, from thermal power plants to hydroelectric plants, has to throttle back. Obviously, doing so ruins the economics of these dispatchable power sources, but is a big part of why the distorted claim of ‘baseload is dead’ is being made.

Chaos Management

Suffice it to say that having the entire grid adapt to PV solar and wind farms – whose output can and will fluctuate strongly over the course of the day – is not an incredibly great plan if the goal is to keep grid costs low. Not only can these forms of variable renewable energy (VRE) only be curtailed, and not ramped up, they also add thousands of kilometers of transmission lines and substations to the grid due to the often remote areas where they are installed, adding to the headache of grid management.

Although curtailing VRE has become increasingly more common, this inability to be dispatched is a threat to the stability of the national grids of countries that have focused primarily on VRE build-out, not only due to general variability in output, but also because of “anticyclonic gloom“: times when poor solar conditions are accompanied by a lack of wind for days on end, also called ‘Dunkelflaute’ if you prefer a more German flair.

What we realistically need are generators that are dispatchable – i.e. are available on demand – and can follow the demand – i.e. the load – as quickly as possible, ideally in the same generator. Basically the grid controller has to always have more capacity that can be put online within N seconds/minutes, and have spare online capacity that can ramp up to deal with any rapid spikes.

Although a lot is being made of grid-level storage that can soak up excess VRE power and release it during periods of high demand, there is no economical form of such storage that can also scale sufficiently. Thus countries like Germany end up paying surrounding countries to accept their excess power, even if they could technically turn all of their valleys into pumped hydro installations for energy storage.

This makes it incredibly hard to integrate VRE into an electrical grid without simply hard curtailing them whenever they cut into online dispatchable capacity.

Following Dispatch

Essential to the health of a grid is the ability to respond to changes in demand. This is where we find the concept of load-following, which also includes dispatchable capacity. At its core this means a power generator that – when pinged by the grid controller (transmission system operator, or TSO) – is able to spin up or down its power output. For each generator the response time and adjustment curve is known by the TSO, so that this factor can be taken into account.

The failure of generators to respond as expected, or by suddenly dropping their output levels can have disastrous effects, particularly on the frequency and thus voltage of the grid. During the 2025 Iberian peninsula blackout, for example, grid oscillations caused by PV solar farms caused oscillation problems until a substation tripped, presumably due to low voltage, and a cascade failure subsequently rippled through the grid. A big reason for this is the inability of current VRE generators to generate or absorb reactive power, an issue that could be fixed with so-called grid-forming converters, but at significant extra cost to the VRE generator owners, as this would add local energy storage requirements such as batteries.

Typically generators are divided into types that prefer to run at full output (baseload), can efficiently adjust their output (load follow) or are only meant for times when demand outstrips the currently available supply (peaker). Whether a generator is suitable for any such task largely depends on the design and usage.

This is where for example a nuclear plant is more ideal than a coal plant or gas turbine, as having either of these idling burns a lot of fuel with nothing to show for it, whereas running at full output is efficient for a coal plant, but is rather expensive for a gas turbine, making them mostly suitable for load-following and peaker plants as they can ramp up fairly quickly.

The nuclear plant on the other hand can be designed in a number of ways, making it optimized for full output, or capable of load-following, as is the case in nuclear-heavy countries like France where its pressurized water reactors (PWRs) use so-called ‘grey control rods’ to finely tune the reactor output and thus provide very rapid and precise load-following capacities.

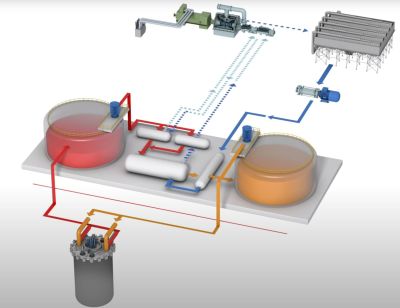

There’s now also a new category of nuclear plant designs that decouple the reactor from the steam turbine, by using intermediate thermal storage. The Terrapower Natrium reactor design – currently under construction – uses molten salt for its coolant, and also molten salt for the secondary (non-nuclear) loop, allowing this thermal energy to be used on-demand instead of directly feeding into a steam turbine.

This kind of design theoretically allows for a very rapid load-following, while giving the connected reactor all the time in the world to ramp up or down its output, or even power down for a refueling cycle, limited only by how fast the thermal energy can be converted into electrical power, or used for e.g. district heating or industrial heat.

Although grid-level storage in the form of pumped hydro is very efficient for buffering power, it cannot be used in many locations, and alternatives like batteries are too expensive to be used for anything more than smoothing out rapid surges in demand. All of which reinforces the case for much cheaper and versatile dispatchable power generators.

Grid Integration

Any power generator on the grid cannot be treated as a stand-alone unit, as each kind of generator comes with its own implications for the grid. This is a fact that is conveniently ignored when the so-called Levelized Cost of Energy (LCoE) metric is used to call VRE the ‘cheapest’ of all types of generators. Although it is true that VRE have no fuel costs, and relatively low maintenance cost, the problem with them is that most of their costs is not captured in the LCoE metric.

What LCoE doesn’t capture is whether it’s dispatchable or not, as a dispatchable generator will be needed when a non-dispatchable generator cannot produce due to clouds, night, heavy snow cover, no wind or overly strong wind. Also not captured in LCoE are the additional costs occurred from having the generator connected to the grid, from having to run and maintain transmission lines to remote locations, to the cost of adjusting for grid frequency oscillations and similar.

Ultimately these can be summarized as ‘system integration costs’, and they are significantly tougher to firmly nail down, as well as highly variable depending on the grid, the power mix and other variables. Correspondingly the cost of electricity from various sources is hotly debated, but the consensus is to use either Levelized Avoided Cost of Energy (LACE) or Value Adjusted LCoE (VALCoE), which do take these external factors into account.

As addressed in the linked IEA article on VALCoE, an implication of this is that the value of VREs drop as their presence on the grid increases. This can be seen in the above graph based on 2020-era EU energy policies, with the graphs for the US and China being different again, but China’s also showing the strong drop in value of PV solar while wind power is equally less affected.

A Heated Subject

It is unfortunate that energy policy has become a subject of heated political and ideological furore, as it should really be just as boring as any other administrative task. Although the power industry has largely tried to stay objective in this matter, it is unfortunately subject to both political influence and those of investors. This has led to pretty amazing and breakneck shifts in energy policy in recent years, such as Belgium’s phase-out of nuclear power, replacing it with multiple gas plants, to then not only decide to not phase out its existing nuclear plants, but also to look at building new nuclear.

Similarly, the US has and continues to see heated debates on energy policy which occasionally touch upon objective truth. Unfortunately for all of those involved, power grids do not care about personal opinions or preferences, and picking the wrong energy policy will inevitably lead to consequences that can cost lives.

In that sense, it is very harmful that corner stones of a healthy grid such as baseload, reactive power handling and load-following are being chipped away by limited metrics such as LCoE and strong opinions on certain types of power technologies. If we cared about a stable grid more than about ‘being right’, then all VRE generators would for example be required to use grid-forming converters, and TSOs could finally breathe a sigh of relief.

This articles is written by : Nermeen Nabil Khear Abdelmalak

All rights reserved to : USAGOLDMIES . www.usagoldmines.com

You can Enjoy surfing our website categories and read more content in many fields you may like .

Why USAGoldMines ?

USAGoldMines is a comprehensive website offering the latest in financial, crypto, and technical news. With specialized sections for each category, it provides readers with up-to-date market insights, investment trends, and technological advancements, making it a valuable resource for investors and enthusiasts in the fast-paced financial world.