Debian, Arch, Slackware? Ubuntu, Open Suse, Mint? Knoppix, Tails, Parted Magic? KDE, Gnome, Cinnamon? Anyone who deals with Linux has to process and categorize dozens of names. A few safe claims can help as landmarks.

If you want to install Linux, you really are spoiled for choice: There are currently around 250 distributions available for end users, the vast majority of them free of charge.

Do you have to know or even try out 250 distributions to find the right one?

Certainly not: 80 to 90 percent can be filtered out in advance. In this article, I’ll present the best systems and work out the differences, advantages, and weaknesses.

Main strains with Debian dominance

The only thing that unites all Linux distributions is the Linux kernel. On this basis, there are five main strains on which the vast majority of distributions (derivatives) are based:

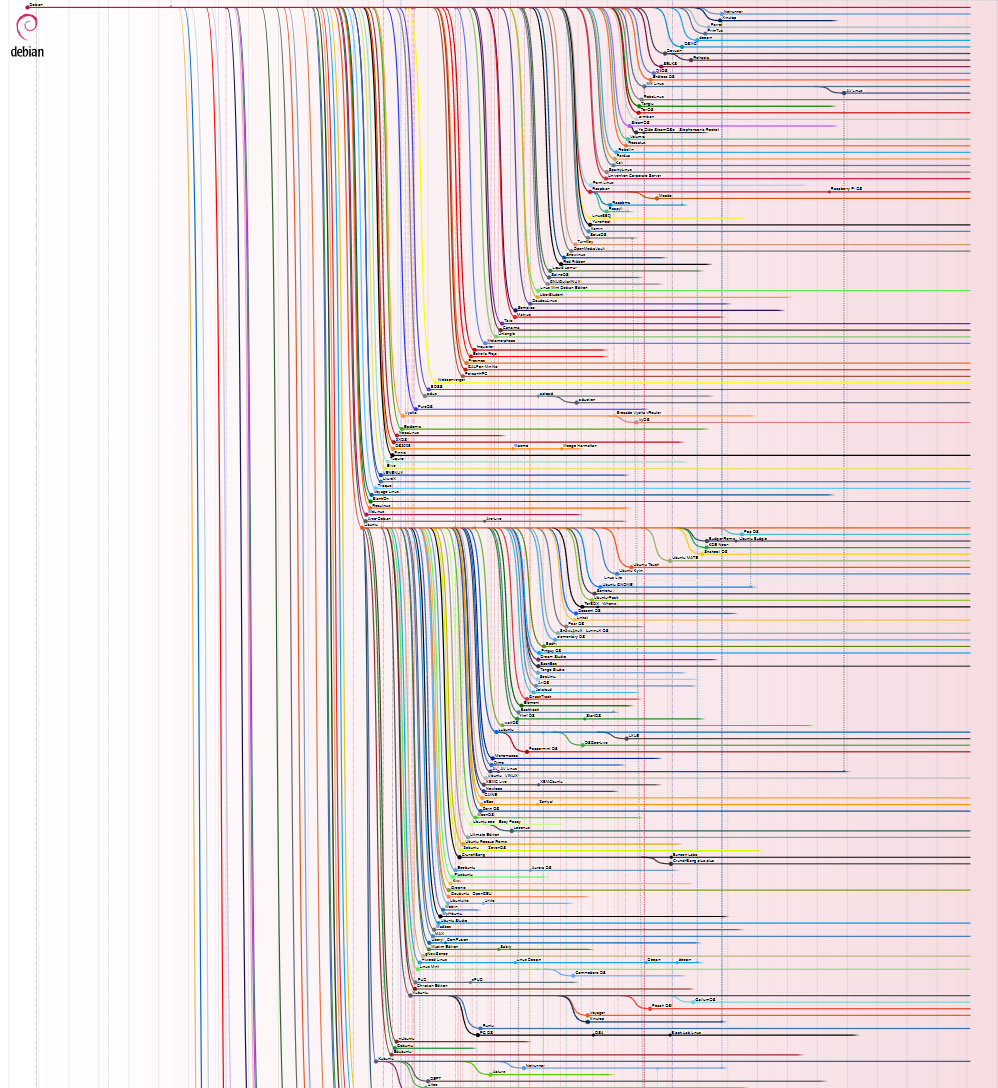

- Debian Linux: around 125 active distributions, including Debian, Raspbian, Knoppix, Ubuntu with numerous other derivatives such as Linux Mint

- RedHat/Fedora: around 25 active distributions, including Fedora, RHEL, Alma Linux

- Arch Linux: around 20 active distributions, including Manjaro, Endeavour-OS)

- Slackware: around 10 active distributions, including Porteus, Slax, and a handful more, if you still want to count Open Suse as Slackware-based

- Gentoo Linux: around eight active distributions, including Redcore Linux

- In addition, there are numerous independent distributions such as Solus-OS, Clear Linux, or Puppy Linux and — for the sake of completeness — the Android mobile system.

Debian therefore has far more successors than all other Linux strains combined. The more than 50 Ubuntu derivatives alone add up to more systems than any other main Linux strain.

The main reasons for the spread of Debian are its compactness, flexibility, and stability (in the most widely used “stable” branch) and the reliable package management with a huge selection of software.

Many derivatives such as Linux Mint, Elementary OS, Bodhi Linux, Zorin-OS, or Bunsenlabs do not reveal their Debian or Ubuntu ancestry in their names.

Knoppix, Raspbian, or the NAS system Open Media Vault are also based on Debian.

This picture is only intended to convey the quantities. These are half of the Debian derivatives with the Ubuntu node.

Foundry

The user and desktop area is dominated by comfortable Debian systems such as Ubuntu, Mint, or Elementary OS. The bottom line is that Debian systems are the first choice for beginners, but also for many pragmatic Linux connoisseurs. The only disadvantage of Debian and others may be somewhat outdated software versions.

Most Gentoo-, Slackware-, Red Hat- and Arch-based systems are not suitable for the majority, but are islands for Linux connoisseurs and for specialized areas of application. The Gentoo base is practically dying out after the end of Sabayon and the switch from System Rescue CD to the Arch base.

However, there are some notable exceptions with Arch, etc.:

Arch Linux: There are two particularly popular distributions here: Endeavour-OS is a very fast Linux with a graphical installer, but requires some Linux experience in everyday use. Manjaro with its graphical installer and package manager is probably the most convenient Arch Linux, but is also not a beginner’s system.

Red Hat: Fedora Workstation is focused on innovation, less on stability. The “Anaconda” installer used here cannot compete with the simpler Debian/Ubuntu alternatives (Ubiquity, Calamares).

Slackware: Porteus is designed as a live system (no installation) and is the first choice for a mobile and fast surfing system. Open Suse is basically based on Slackware, but is now considered independent.

For more than a decade, it was almost the only Linux aimed at the PC desktop with graphical operation and configurability.

The distribution has lost importance and now tends more towards innovation (e.g. BTRFS file system) and less towards beginner-friendliness. Nevertheless, Open Suse (“Leap“) remains a rock-solid choice.

Package formats and containers

A desktop user may not care whether their VLC player or Office program runs under Debian or Arch. The software is the same in both cases.

However, as all the main strains mentioned use a different package format and different tools when obtaining the software, the choice of system for the software used plays an important role.

Once you are used to the DEB package format (Debian, Ubuntu & Co., Linux Mint) and the apt terminal tool responsible for this, the changeover to RPM (Slackware, Red Hat, Open Suse), Tar.xz (Arch) or even Portage (Gentoo) is a significant hurdle and vice versa.

Package management differs technically in terms of recognizing package dependencies and also in terms of operation.

Graphical software centers of desktop systems should not be relied on exclusively, as they only offer a subset of the software sources. Fundamental knowledge of the respective terminal package manager is therefore important.

The package format for installations and updates differs significantly between the main Linux strains. Anyone who is used to Debian or Arch will remain loyal for this reason.

Foundry

Apt (DEB packages under Debian/Ubuntu), Zypper (RPM packages under Open Suse) and Yum (RPM packages under Red Hat) can be considered relatively simple.

You have to get used to the very concise syntax of Pacman (Arch), although only a handful of commands are required for the essentials (update, installation, uninstallation, search).

Familiarizing yourself with Emerge and Gentoo’s Portage package format will be too much for normal users.

The Snap and Flatpak container formats require independent management. This, their package sizes, and the increased system complexity are annoying or even off-putting for many users.

If you want to avoid Snaps, you have to avoid all official Ubuntus (Ubuntu, Kubuntu, Lubuntu, Xubuntu, UbuntuMate/Budgie/Cinnamon/Unity).

With Flatpak, the situation is more relaxed because here, as a rule, only the offer in the form of the management software is available, but no binding pre-installed Flatpak software. Candidates with a pre-installed Flatpak environment are Linux Mint, Elementary OS, Endless OS, Fedora, Tuxedo-OS, Zorin-OS.

Different release models

All Linux distributions provide standard package sources to supply the respective operating system with software and updates. There are clearly differentiated release models, which are essential for up-to-dateness and stability, but are not always communicated as clearly as they should be.

Fixed: This is the regular and predominant release model with a quasi-static standard system. The fixed model is not only typical for Debian/Ubuntu/Mint, but is standard almost everywhere beyond Arch Linux.

The kernel and system remain conservatively in their original state and updates only correct the current security problems.

In the case of LTS long-term versions, function and kernel updates are carried out via periodic point releases.

In general, this model guarantees high stability for the desktop, and even more so for server systems. However, the application software from the package sources can become relatively outdated over the years (with the exception of browsers).

Rolling: This model is the rule for Arch-based distributions (Arch, Endeavour-OS, Manjaro), but can also be found elsewhere as an optional variant: Examples include Debian Sid, the Ubuntu-based Rhino Linux, or Open Suse “Tumbleweed”. The independent Solus OS is also a rolling release.

Rolling releases do not recognize system versions, but keep the Linux kernel, drivers, system, and software permanently up to date — with certain risks of incompatible components.

Rolling releases are suitable for users who tend to be competent, who always want to stay up to date and can fix any problems themselves. Semi-rolling releases such as MX Linux, Antix, KDE Neon, or Tuxedo-OS are hybrids between fixed and rolling.

Immutable: The young, extremely secure release model “Immutable Linux” is more restrictive than the fixed model and strictly separates the core system and software. Apart from updates, the core system is static and unchangeable for both users and software.

For application software, the container formats Flatpak and Snap are used, which do not interfere with the core system.

Prominent candidates are Fedora Silverblue, Endless OS, and soon a variant of Debian 13.

However, the immutable model is hardly recommended for normal users: The range of software is limited, the read-only system is too inflexible for server tasks, and the same applies to driver updates.

Origin and sustainability

In the mass of distributions on offer, some candidates may appear to be the perfect solution at first glance. However, typical desktop users or even Linux beginners should not get involved with exotics.

Linux projects from small development teams may quickly become obsolete or have shortcomings that are not immediately recognizable even after trying out the live system. A lack of language support or a mixed-language system are among the most common, but by no means the most serious shortcomings.

Distributions and desktops

A user-friendly interface is at least as important to many users as the familiar package format or release model. However, distributions and desktops are a complicated subject.

Although the well-established statement that the desktop under Linux is merely an interchangeable software application is technically true, it is still not correct. If you choose a distribution with the wrong desktop, you will regularly be disappointed by a “real” desktop installed afterwards.

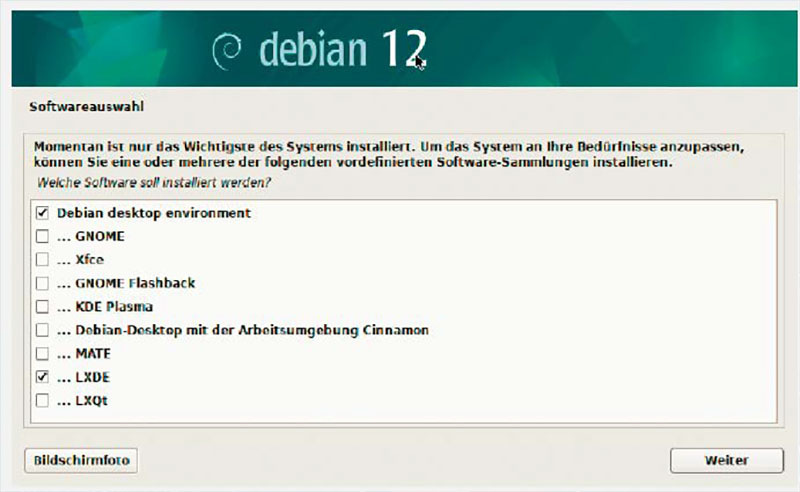

This also applies to distributions without a default desktop with Netinstaller (such as Debian, Open Suse, Parrot-OS), which install the desktop selected by the user. As flexible as this may seem, the result is always an unambitious standard desktop that requires reworking and possibly further installations.

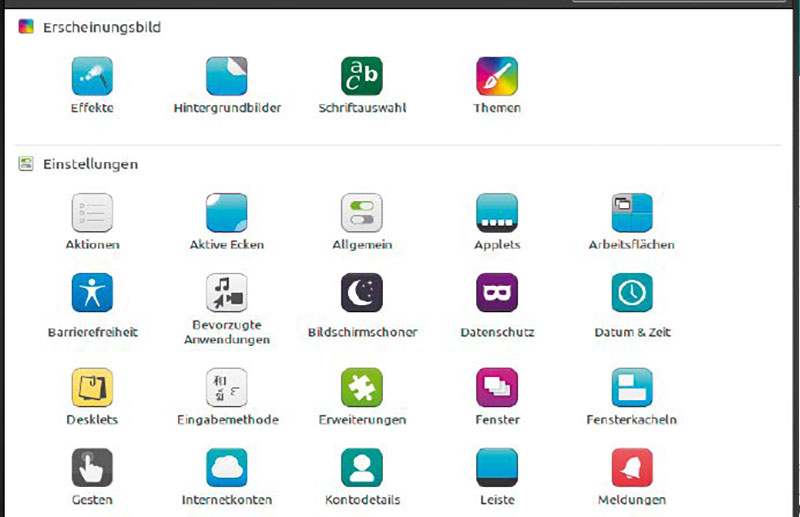

Desktop and distribution selection: The widest possible range of graphical management tools is important if terminal knowledge is lacking.

Foundry

Practically speaking: It is advantageous to choose distributions that are clearly or even unambiguously committed to a desktop. Here you can assume that the interface is optimized and delivered with all the associated components.

Examples of distributions that clearly serve a desktop are official Ubuntu flavors such as Kubuntu (KDE), Xubuntu (XFCE), Lubuntu (LXQT), as well as Elementary OS (Pantheon), KDE Neon (KDE), Bodhi Linux (Moksha), or Bunsenlabs (Openbox).

Most distributions avoid the restriction to one desktop and therefore offer several interfaces, but favor at least one standard. It is practically always best to choose this standard desktop — and if this desktop is not desired, it is better to choose a different distribution.

Examples of distributions that clearly favor a specific desktop are Linux Mint (Cinnamon), Solus-OS (Budgie), or Parrot-OS Home (XFCE).

The Linux desktops

If you expect — without a terminal — the most complete graphical use possible for software installation, system configuration, drive management, and desktop customization, you cannot choose just any Linux desktop and therefore not just any distribution.

The desktop for Linux systems is in principle freely selectable, as here with the Debian Netinstaller. However, you are better off with a distribution with a pre-installed standard desktop.

Foundry

KDE Plasma: With its configuration centers and system tools, KDE is the undisputed leader among Linux desktops. However, KDE is complex and not always beginner-friendly. Other obvious distributions would be Kubuntu, KDE Neon, or Opensuse “Leap”.

Cinnamon: This desktop is probably the best Linux interface at the moment, combining a wealth of functions with (still) clear operation. Linux Mint, Ubuntu Cinnamon, and others offer the latest and most complete Cinnamon.

Gnome: This desktop is unconventional, but functional and complete, although the administration area (“Settings”) is more confusing than KDE or Cinnamon. Typical Gnome distributions are Ubuntu, Fedora, or Pop-OS.

Mate: The Mate interface still ranks among the complete desktops in that almost all administrative tasks can be performed graphically. Nevertheless, it only serves as the standard desktop under Ubuntu Mate, although many distributions offer it as an option.

Budgie: The Gnome-based desktop makes Gnome more traditional again, but has the same confusing settings center and its own customization tools that take some getting used to. The traditional distributions are Solus-OS and Ubuntu Budgie.

XFCE: The conservative desktop is easy to use and customize, but has slight deficits compared to the “big” interfaces when it comes to system tools. Model distributions are Xubuntu, MX Linux, or Voyager-OS.

LXQT: This desktop is standard in Lubuntu alone, but optional in many distributions. Although LXQT borrows configuration tools from its big brother KDE, complete graphical system administration reaches its limits here.

Pantheon: The desktop with a Mac look is attractive, but very reduced. System settings and customizations only offer the essentials. Pantheon is developed by the Elementary OS distribution and is standard there.

LXDE/Moksha/Openbox/Fluxbox: These interfaces are representative of a number of others that a user can select specifically because they like them or because they need to save resources. They offer few configuration tools and delegate system administration to the terminal.

Distributions that rely on such desktops are generally optimized for economy or live operation, such as Knoppix (LXDE), Bodhi Linux (Moksha), Bunsenlabs (Openbox), and MX Linux (Fluxbox).

More hard facts about Linux distributions

Wikipedia with hardcore information: The article “Comparison of Linux distributions” provides technical details on a large number of Linux distributions in several individual tables.

Foundry

The English-language Wikipedia website “Comparison of_Linux_distributions” shows information on all important distributions in sophisticated tables.

For example, the existence of an installable live system or a graphical installer, the general orientation, the standard file system, the standard desktop or the number of software packages for each distribution can be researched here. These tables are excellent decision-making aids for a strategic distribution search.

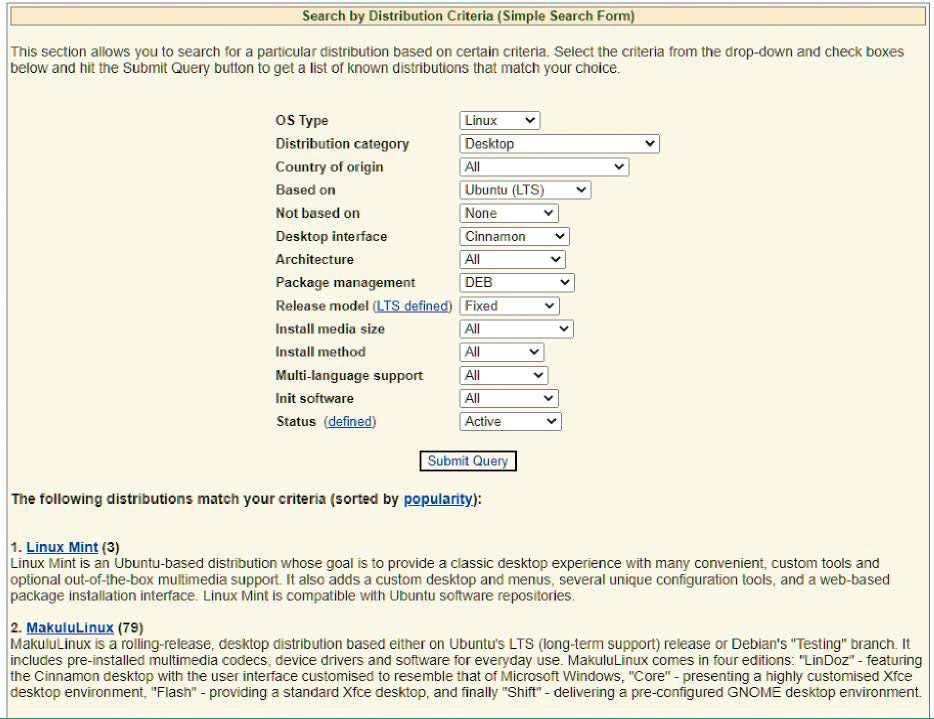

The Distrowatch website always provides up-to-date information on all Linux distributions — including servers, exotics, and extinct dinosaurs. In addition to basic data on origin and orientation, there is always a brief, rarely in-depth system characterization.

A simple distribution search by name can be found at the top left of the homepage. The real highlight, however, is the search filter at distrowatch.com/search.php.

Provided you have some knowledge of Linux, there is no other way to get a quicker answer to the question of whether there is an Arch-based distribution with Netinstaller and Budgie desktop.

Advanced search filters on Distrowatch: The well-maintained database enables technical selection filters for a targeted system search.

Foundry

This articles is written by : Nermeen Nabil Khear Abdelmalak

All rights reserved to : USAGOLDMIES . www.usagoldmines.com

You can Enjoy surfing our website categories and read more content in many fields you may like .

Why USAGoldMines ?

USAGoldMines is a comprehensive website offering the latest in financial, crypto, and technical news. With specialized sections for each category, it provides readers with up-to-date market insights, investment trends, and technological advancements, making it a valuable resource for investors and enthusiasts in the fast-paced financial world.