As Hackaday writers we don’t always know what our colleagues are working on until publication time, so we all look forward to seeing what other writers come up with. This week it was [Al Williams] with “Things Your TV No Longer Needs“, a range of gadgets from the analogue TV era, now consigned to the history books. On the bench here is a device that might have joined them, so in taking a look at it now it’s by way of an addendum to Al’s piece.

When VHF Was Not Enough

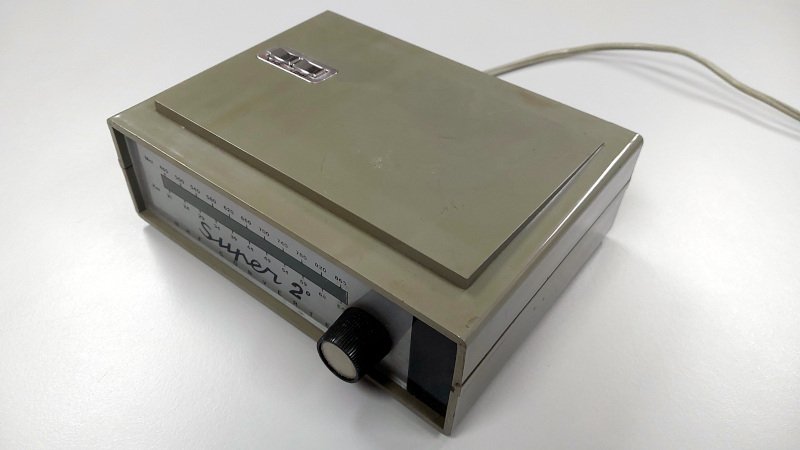

In a Dutch second-had store while on my hacker camp travels this summer, I noticed a small grey box. It was mine for the princely sum of five euros, because while I’d never seen one before I was able to guess exactly what it was. The “Super 2” weighing down my backpack was a UHF converter, a set-top box from before set-top boxes, and dating from the moment around five or six decades ago when that country expanded its TV broadcast network to include the UHF bands. If your TV was VHF it couldn’t receive the new channels, and this box was the answer to connecting your UHF antenna to that old TV.

It’s a relatively small plastic case about the size of a chunky paperback book, on the front of which is a tuning knob and scale in channels and MHz, on the top of which are a couple of buttons for VHF and UHF, and on the back are a set of balanced connectors for antennas and TV set. It’s mains powered, so there’s a mains lead with an older version of the ubiquitous European mains plug. Surprisingly it comes open with a couple of large coin screws on the underside, so it’s time to take a look inside.

Inside: A Familiar Sight

At first sight it’s fairly simple: a conventional mains DC power supply with no regulator and a metal tuner can. The scale mechanism is a string-and-gears affair, something quite common back in the day but a rare sight today. Unclipping the lid of the tuner can reveals its secret, this is the front end of a UHF TV tuner modified slightly to produce an output on a VHF broadcast channel. We’ve covered UHF TV tuners in the past, but if you’ve never encountered them here’s how they worked. Inside the can is a series of cavity tuned circuits containing two transistors. One of them is wired as an RF amplifier that works on the signal from the antenna, and the other is an oscillator. By mixing the amplified antenna signal with the oscillator output it’s possible to filter out an intermediate frequency, which is their difference. This was always 36 MHz, chosen because it lies just below the VHF broadcast band, and since this tuner needs to feed an unmodified VHF television, its output frequency will be a bit higher. We’re guessing that it’s been modified for a 41.25 MHz output, corresponding to the European VHF channel 1.

So in front of me I have a European thing that your TV no longer needs, and it’s one that probably didn’t have a very long market life. It’s a snapshot of a moment in consumer electronics history, when the number of channels could be counted on far less than the fingers of a hand. With analogue TV now long switched off it’s not even got a use any more except as a curio, so it joins the pile of museum-pieces alongside the 8-track player. Meanwhile if you’d like to see how an American city handled the UHF transition, we’ve been back to 1950s Portland, too.