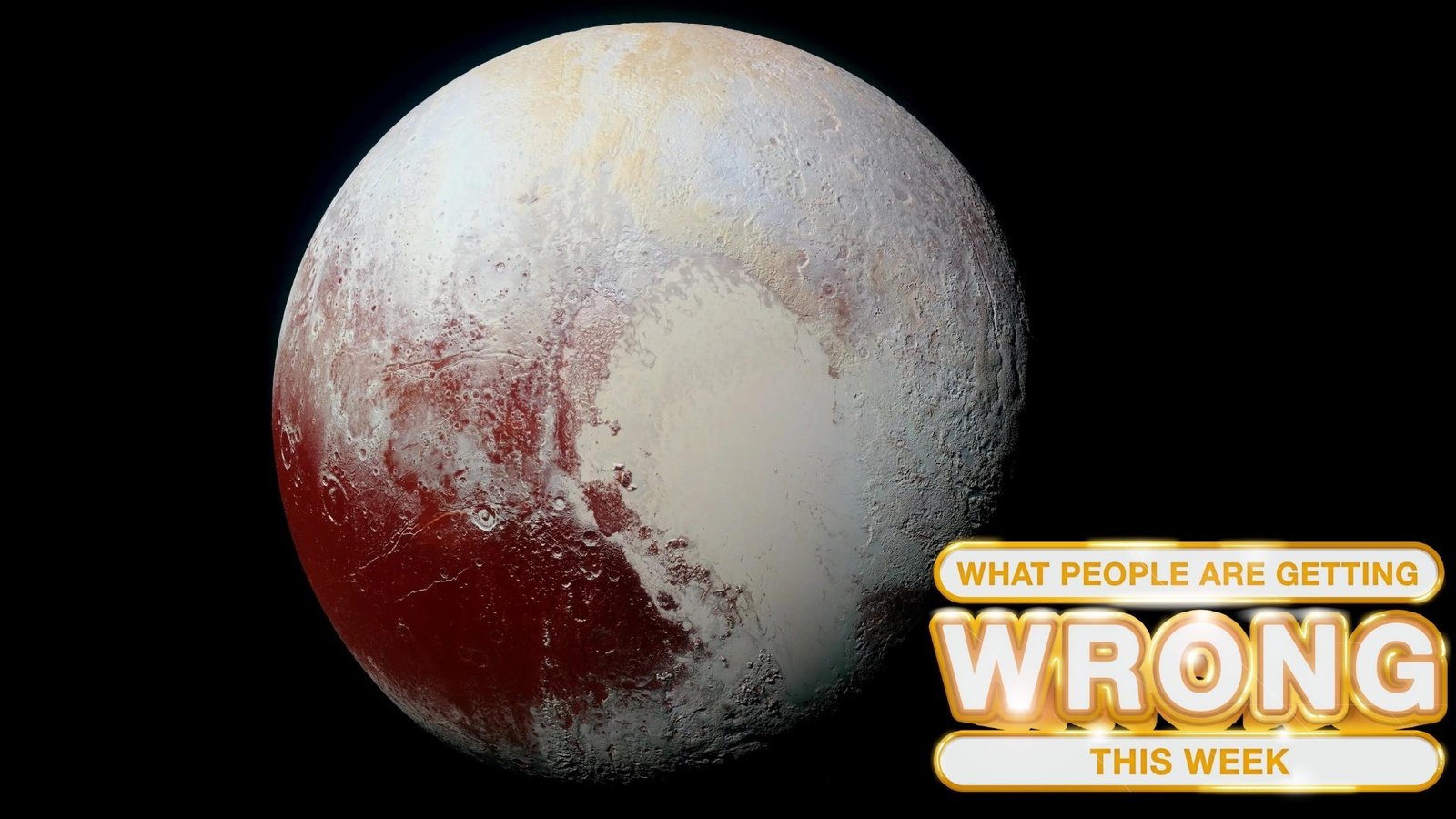

We are less than two weeks away from the 95th anniversary of the discovery of Pluto, the ice-caked, rocky sphere orbiting around 3.7 billion miles from the sun. To mark the occasion, The Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, where Pluto was discovered, is hosting its sixth annual “I Heart Pluto” festival. But should they? Is Pluto even a planet?

According to a recent YouGov poll, 35% of Americans think Pluto is not a planet. It’s something else, according to them. But they are all wrong—kind of. To get to the bottom of Pluto’s planet status, I tracked down planetary scientist Dr. Will Grundy—who you might recognize from academic papers like “Measurement of D/H and 13C/12C ratios in methane ice on Eris and Makemake: Evidence for internal activity,”— and asked him flat out: Pluto, planet or fraud?

The case for Pluto’s planet-ness

According to Dr. Grundy, Pluto is a planet. “I use the word ‘planet’ to refer to it, and most of the planetary science community does too,” Grundy said. “Pluto’s got everything I like in a planet, in spades. It’s got a satellite system. It’s got atmosphere with interesting weather patterns. It’s got very complicated seasonal cycles. It’s got all kinds of active geology going on… it’s got everything you want.”

So Pluto is a planet. Case closed. Well maybe not totally closed.

The case against Pluto’s planet-ness

According to The International Astronomical Union, Pluto is not a planet. The IAU shook the world in 2006 when it took Pluto’s status as a planet away.

According to the IAU, to be a planet, you must do all of the following:

-

Orbit the sun.

-

Have enough mass for your own gravity to pull you into a nearly round shape.

-

Have cleared the area around your orbit of other significant objects.

Like my friend Dave, Pluto has only met two of these criteria. That third one is too much for Pluto. Therefore, the IAU says Pluto can’t sit at the cool kids table with Venus and Saturn; its proper place is with bitch-ass dwarf planets like Quaoar, Sedna, and Orcus.

Why Pluto’s “planet” status is an issue

Pluto’s demotion was partially caused by us getting better at spotting planets (or “dwarf planets,” if you prefer). In the early 2000s, astronomers identified Haumea, Eris, Makemake, and other balls that orbit our sun. They’d all have to be call “planets” if the older definition of the word was used. So the IAU punted. “They had a moment of a crisis of strength of will,” Grundy said. “They freaked out because they were realizing that there was going to be a whole bunch of additional planets, and that just panicked them.”

So the cowards at the IAU came up with guidelines for what makes a planet a planet, based, seemingly, on the traditional planets we all know and love, and read about in astrology books. According to many scientists, this was a mistake. “They adopted a definition from folk culture in place of the scientific definition, and it’s embarrassing for them to have done this,” Grundy said. “They didn’t want to have to be announcing a new planet every year and then have some expectation that, you know, school kids are gonna have to memorize 15 of them, and now three years later, it’s 20 of them, and so on and so forth.”

According to Grundy, the more planets, the better. “Have you ever met a little kid that likes dinosaurs and is offended when they discover another one?” Grundy asked.

Is Pluto actually two planets?

How about this to blow your mind: Pluto is two planets. Boom! Shots fired. Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, is almost half the size of Pluto. “I would consider Charon big enough to be a planet,” Grundy said. “It has geology and all kinds of processes going on. What more could you ask for?”

If it sounds like just stretching the definition of “planet” to mean whatever you want, that’s how words work. The scientific community talks about planets more than anyone else, and they don’t have a problem with it using the word in all kinds of ways, including in reference to Pluto. “If you listen to a talk on planetary geology, you’ll hear the word used in a different way than if you go to a talk on the early evolution of the solar system,” Grundy said. “It really just depends on your focus.”

Pluto doesn’t care if it’s a planet or not

The question of whether Pluto is a planet or not isn’t really about the celestial body. It’s about the way we label things, and the way the universe refuses to conform to human taxonomies. No matter what we call Pluto, it’ll still be out there, doing its Pluto thing.

“Textbook authors seem to always seek authority. They want a definitive answer, because they don’t want to be wrong. But that’s not really the way nature works. Nature is very messy and muddy,” Grundy said. “We used to categorize whales with other fishes because they lived in the ocean. We don’t do that anymore, because we know they’re mammals, and we know the the phylogenetic origins. But why do we care more about phylogenetic origins than we care about location? The mindset evolves, and it doesn’t evolve in everyone at the same rate and in the same direction.”

This articles is written by : Nermeen Nabil Khear Abdelmalak

All rights reserved to : USAGOLDMIES . www.usagoldmines.com

You can Enjoy surfing our website categories and read more content in many fields you may like .

Why USAGoldMines ?

USAGoldMines is a comprehensive website offering the latest in financial, crypto, and technical news. With specialized sections for each category, it provides readers with up-to-date market insights, investment trends, and technological advancements, making it a valuable resource for investors and enthusiasts in the fast-paced financial world.